Sedentary Lifestyle Related to Succesful Again G

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Sedentary behavior and wellness outcomes amongst older adults: a systematic review

BMC Public Wellness book 14, Article number:333 (2014) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Groundwork

In the terminal decade, sedentary behavior has emerged as a new risk cistron for health. The elderly spend nearly of their awake time in sedentary activities. Despite this high exposure, the bear upon of this sedentary behavior on the health of this population has not yet been reviewed. We systematically reviewed evidence for associations betwixt sedentary behavior and multiple health outcomes in adults over sixty years of age.

Methods

We searched the Medline, Embase, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, PsycINFO, CINAHL, LILLACS, and Sedentary Research Database for observational studies published upwards to May 2013. Additionally, we contacted members of the Sedentary Behaviour Research Network to place articles that were potentially eligible. Later on inclusion, the methodological quality of the evidence was assessed in each study.

Results

We included 24 eligible articles in our systematic review, of which merely 2 (8%) provided loftier-quality evidence. Greater sedentary time was related to an increased risk of all-crusade mortality in the older adults. Some studies with a moderate quality of evidence indicated a relationship between sedentary behavior and metabolic syndrome, waist circumference, and overweightness/obesity. The findings for other outcomes such equally mental health, renal cancer cells, and falls remain insufficient to depict conclusions.

Determination

This systematic review supports the relationship between sedentary beliefs and mortality in older adults. Additional studies with loftier methodological quality are still needed to develop informed guidelines for addressing sedentary behavior in older adults.

Background

Globally, the older adult population has increased substantially, and it is estimated to reach approximately 22% of the world's population past 2050 [i, 2]. The run a risk of non-infectious disease and disability increases with historic period, providing a challenge for health and social care resources [3]. The World Health Organization has created many recommendations for behavior alter to reduce the burden of non-communicable diseases and disabilities amidst the elderly [four]. It is well established that physical activity plays a key role in the prevention of such diseases due to its close relationship with many of the chronic diseases and disabilities that largely affect the elderly, such as cardiovascular illness, cancer, type 2 diabetes, accidental falls, obesity, metabolic syndrome, mental disorders, and musculoskeletal diseases [5, 6].

Notwithstanding, in the final decade, sedentary behavior has emerged every bit a new risk factor for wellness [7–9]. Sedentary behaviors are characterized past any waking activity that requires an energy expenditure ranging from 1.0 to one.5 basal metabolic charge per unit and a sitting or reclining posture [10]. Typical sedentary behaviors are television viewing, computer employ, and sitting time [10]. Epidemiological studies on dissimilar historic period groups show that a considerable amount of a human being'due south waking hours are spent in sedentary activities, creating a new public health claiming that must be tackled [11, 12]. The scientific written report of sedentary behavior has become pop in recent years. In fact, several systematic reviews of sedentary behaviors and wellness outcomes among children, adolescents, [13–15] and adults [eleven, sixteen–19] take recently been published. However, insights from these systematic reviews are limited for several reasons. Firstly, some of these systematic reviews did non evaluate the quality of show of the reviewed articles [17, 16]. Secondly, some reviews included subjects with a wide age range (i.eastward., >eighteen years) [xvi, 17]. Therefore, it is currently assumed that the deleterious health effects attributed to sedentary behaviors are similar among both adults (>18 years) and the elderly (>60 years). However, it has been observed that some cardiovascular adventure factors (i.east., smoking, obesity, and consumption of alcohol) are less predictive of mortality in a large sample of Scandinavians aged 75 years or older [20].

Furthermore, compared with other age groups, older adults are the almost sedentary. Findings from studies in the US and Europe reported that objectively measured sedentary time was higher in those who were older than 50 years [12] and 65 years, [21] respectively. In improver, it has been reported that adults older than 60 years spend approximately 80% of their awake time in sedentary activities which represents 8 to 12 hours per day [12, 21, 22]. Similarly, Hallal et al. conducted a global assessment in more than than lx countries and found that the elderly had the highest prevalence of reporting a minimum of 4 hours of sitting time daily [23]. Despite this loftier exposure in the elderly, the wellness furnishings of sedentary behavior in this population have not even so been reviewed. Due to this noesis gap, we systematically reviewed evidence to look for associations between sedentary behavior and multiple health outcomes in adults over 60 years of age.

Methods

Identification and selection of the literature

In May 2013, nosotros searched the following databases: Medline, Excerpta Medica (EMBASE), Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, PsycINFO, Cumulative Alphabetize to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Literatura Latino-Americana eastward practice Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILLACS), and the Sedentary Behavior Research Database (SBRD).

The cardinal-words used were as follows: exposure (sedentary behavior, sedentary lifestyles, sitting time, television viewing, driving, screen-fourth dimension, video game, and computer); primary outcome (mortality, cardiovascular affliction, cancer, type 2 diabetes mellitus); and secondary consequence (accidental falls, frail elderly, obesity, metabolic syndrome, mental disorders, musculoskeletal diseases). Further information regarding the search strategy is included in Additional file i. Co-ordinate to the purpose of this systematic review, observational studies (cross-sectional, instance–control, or accomplice) involving older adults (all participants >sixty years), with no restriction of linguistic communication or date, were selected in the screening step.

In addition, we contacted the Sedentary Behaviour Enquiry Network (SBRN) members in July 2013 to asking references related to sedentary behavior in older adults. The SBRN is a non-profit arrangement focused on the scientific network of sedentary behavior and wellness outcomes. Additional information nigh the SBRN can exist found elsewhere (http://www.sedentarybehaviour.org/).

The studies retrieved were imported into the EndNote Web® reference management software to remove any duplicates. Initially, titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers (LFMR and JPRL). Relevant articles were selected for a full read of the article. Disagreements between the two reviewers were settled by a 3rd reviewer. In addition, the reference lists of the relevant manufactures were reviewed to detect additional articles that were not identified in the previous search strategy.

Studies were excluded if they met the following criteria: 1) Included adults <60 years of age; 2) did non include concrete activity as a covariate; or 3) presented but a descriptive analysis of sedentary behavior.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The data from all of the eligible articles were extracted independently by two reviewers (LFMR and JPRL). The extracted data included the post-obit information: author(s), year, country, age grouping, number of participants, blazon of population (general or patient), type of sedentary behavior, blazon of measurement tool, sedentary definition, adapted confounders, and outcome (Additional file 2: Tabular array S1).

The quality assessment was performed past ii independent reviewers (LFMR, JPRL) and discussed during a consensus meeting. The quality of articles was assessed using the Grades of Recommendation, Cess, Evolution and Evaluation (Form) tool (Table 1). Briefly, the GRADE quality cess tool begins with the design of the study. Studies with an observational pattern beginning with a depression quality (2 points). The studies then lose points based on the presence of the following topics: run a risk of bias (−1 or −2 points), imprecision (−1 or −2 points), inconsistency (−i or −two points), and indirectness (surrogate effect) (−ane or −2 points). Even so, studies gain points if the post-obit criteria are met: a loftier magnitude of outcome (RR ii–5 or 0.five – 0.2) (+ 1 or 2 points), adequate confounding adjustment (+1 point), and a dose–response relationship (+1 indicate). Finally, the quality of the manufactures is categorized equally follows: high (4 points), moderate (3 points), low (2 points), or very low (i point). Further information about Class has been published elsewhere [24].

Results

Search and selection

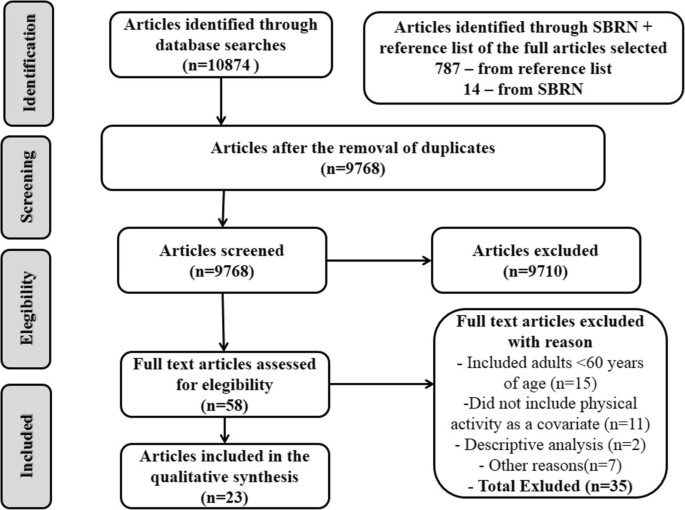

The search included 10874 potentially relevant articles (1301 from Medline, 5190 from EMBASE, 2803 from Web of Science, 184 from CINAHL, 160 from Lillacs, 154 from SportsDiscus, 936 from PsychInfo, and 146 from Sedentary Behavior Research Database). Fourteen additional records were selected from the articles suggested past the SBRN members (Figure i).

Flowchart outlining report selection.

After removing duplicate records, a total of 9768 manufactures remained. Afterwards screening titles and abstracts, 56 full papers were read in their entirety. In addition, 2 articles were constitute in the reference list of these full papers (an additional 787 titles were screened). Of the 58 manufactures, but 23 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The consummate listing of included and excluded manufactures is presented in the Additional file iii.

Methodological quality assessment

Boosted file 2: Table S1 presents the quality assessment of the 23 articles included in the review. Of the 23 manufactures included, sixteen (70%) were cross-exclusive studies, [25–xl] one (4%) was a case–control study, [41] and 6 (26%) were prospective accomplice studies [42–47]. Concerning quality of the evidence, 12 (52%) were evaluated as very low, [25, 26, 29–36, 38, 42] 5 (22%) as low, [39, 41, 43, 44, 48] 4 (17%) as moderate, [28, 37, forty, 45] and 2 (9%) as high quality evidence [46, 47].

Risk of selection bias was identified in nine articles (39%), [25, 28, 29, 31–34, 37, 42, 47] and data bias due to self-reported instruments was plant in 20 articles (83%) [25–27, 31–34, 37, 38, 40–47]. Indirectness (surrogate outcomes) was used in xvi articles (70%), [25–37, 39–41] imprecise results were presented in 14 (61%) articles, [25–27, 30–32, 34–39, 41, 42] and an inconsistent [25] upshot among subgroups was found in ane (4%) article. Most of the articles (northward = 20 – 87%) received an additional point for the adjustment of potential confounders [25–29, 32–39, 41–47]. Eleven (48%) studies gained a point for magnitude of effect [30, 36, 39, viii–42, 44–47] and five (22%) for considering a dose–response relationship [36, 39, 42, 45, 46]. Further details concerning the quality cess of each commodity are presented in the Additional file four.

Sedentary behavior—wellness outcomes

Mortality

Four prospective cohort studies, [43–46] classified as depression, [43] moderate [44] and high quality, [45, 46] investigated the relationship between sedentary behavior and mortality (all-cause, cardiovascular, colorectal cancer, other causes).

Martinez-Gomez et al.'southward [44] study showed that individuals who spent less than 8 hours sitting/day had a lower chance of all-cause mortality (Hr = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.lx to 0.82) when compared with their sedentary peers. In add-on, individuals who were physically active and less sedentary (<viii hours/twenty-four hour period of sitting) showed a lower chance of all cause-bloodshed (Hour 0.44; 95% CI: 0.36 to 0.52) than those who were inactive and sedentary.

Similarly, Pavey et al. [45] found a dose–response human relationship between sitting time and all-cause mortality. Individuals who spent viii–11 hours/mean solar day (HR 1.35; 95% CI 1.09 – 1.66) and more than than 11 hours/mean solar day sitting (HR 1.52; 95% CI 1.17 – 1.98) presented a higher risk of all-cause bloodshed than those who spent less than 8 hours/mean solar day sitting. For each hour/day spent sitting, there was an increase of 3% (Hr one.03; CI 95% ane.01-1.05) in the risk of all-cause bloodshed. Moreover, the risk of all-cause mortality of individuals who were physically inactive (less than 150 minutes/week) and spent 8–xi or more than eleven hours/day sitting increased past 31% (HR 1.31, 95% CI one.07 to 1.61) and 47% (Hour 1.47, CI ane.xv to 1.93), respectively.

In León-Munoz et al., [46] individuals were classified every bit consistently sedentary (>median in 2001 and 2003), newly sedentary (<median in 2001 and > median in 2003), formerly sedentary (>median in 2001 and < median in 2003), and consistently nonsedentary (<median in 2001 and 2003). They found that when compared with the consistently sedentary group, subjects newly sedentary (HR 0.91; 95% CI 0.76 - 1.x), formerly sedentary (0.86; 95% CI 0.70 - 1.05), or consistently not-sedentary (0.75; 95% CI 0.62 - 0.90) were protective confronting all-cause bloodshed.

Examining a colorectal cancer survivor population, Campbell et al. [43] identified that more than six hours per day of pre-diagnosis leisure sitting fourth dimension, when compared with fewer than 3 hours per day, was associated with a college risk of all-cause bloodshed (RR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.68) and mortality from all other causes (not cardiovascular and colorectal cancer) (RR, 1.48; 95% CI 1.05-2.08). Post-diagnosis (colon cancer) sitting time (>6 hours) was associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality (RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.64) and colorectal cancer-specific mortality (RR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.07-2.44).

Metabolic syndrome

Three cross-sectional studies, [25, 35, 36] classified every bit very low [25, 35] and moderate [36] quality, investigated the relationship between sedentary behavior and metabolic syndrome.

Gardiner et al., [25] showed that individuals who spent nearly of their time sitting (highest quartile, >3 hours/day) had an increased odds of having metabolic syndrome (men: OR 1.57; CI 95% 1.02 – two.41 and women: OR 1.56; CI 95% 1.09 – two.24) when compared with their less sedentary peers (lowest quartile, <1.14 hours/day). In the same report, women who watched more television (highest quartile) increased their take chances of metabolic syndrome by 42% (OR one.42; CI 95% 1.01 – 2.01) when compared with those who watched less tv set per day (lowest quartile).

In the aforementioned sense, Gao et al. [36] showed that individuals in the highest quartile (>seven hours/day) of television watching/twenty-four hour period, when compared with those in the everyman quartile (<i hours/day), had an increased odds (OR 2.ii, 95% CI one.1–4.ii) of having metabolic syndrome. In a dose–response relationship, for each hour of television watching/24-hour interval, there was an increase of 19% in the odds (95% CI i.1–1.3; p for trend 0.002) of having metabolic syndrome.

Bankoski et al. [35] found that a greater percentage of the time spent in sedentary behavior increased the adventure of having metabolic syndrome (only quartile 2 vs. quartile one, the hours/mean solar day of each quartile was not reported; OR one.58; 95% CI 1.03 - 2.24), whereas breaks in sedentary time throughout the day protected confronting metabolic syndrome (just quartile 2 vs. quartile one; OR 1.53; 95% CI i.05 - 2.23).

Cardiometabolic biomarkers

Half dozen cross-exclusive studies, [25, 28, 33, 34, 36, 39] classified as of very depression [25, 28, 33, 34] and of moderate quality, [36, 39] investigated the relationship between sedentary beliefs and independent cardiometabolic biomarkers.

Triglycerides

The likelihood of having loftier triglycerides was college in men (Odds Ratio (OR) i.61; 95% CI ane.01-2.58) and women (OR one.66; 95% CI 1.14-2.41) who were in the highest quartile of overall sitting fourth dimension [25]. However, Gao et al. [36] and Gennuso et al. [39] showed that the association between time spent in sedentary beliefs and high triglycerides was not statistically significant.

HDL cholesterol

Gao et al., [36] found that greater time spent viewing goggle box was associated with low HDL cholesterol (2.5; 95% CI ane.0-5.9; p < 0.05). In a written report by Gardiner et al., [25] women in the highest quartile of television viewing and men in the highest quartile of overall sitting time presented an OR for low HDL cholesterol of 1.64 (95% CI 1.06-2.54) and 1.78 (95% CI 1.78; 95% CI 1.05-3.02), when compared with the lowest quartile, respectively. Nonetheless, Gennuso et al. [39] institute that the relationship between time spent in sedentary behavior and low HDL cholesterol was not statistically significant (p = 0.29).

Blood pressure

When compared with the lowest quartile of overall sitting fourth dimension, the OR for high blood pressure in the third quartile was 1.50 (95% CI 1.03-2.xix) [25]. In Gao et al.'s [36] study, greater time viewing television was associated with high blood force per unit area (2.5; 95% CI 1.0-6.0; p < 0.05). However, Gennuso et al. [39] plant that the human relationship between time spent in sedentary behavior and systolic blood pressure (p = 0.09) and diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.32) was not statistically significant.

Plasma Glucose/ Hb1Ac/ Glucose intolerance

Gennuso et al. [39] demonstrated that greater tv set viewing and sedentary time was associated with college plasma glucose (p = 0.04). In Gardiner et al.'s [25] written report, this relationship was observed only in women (1.45; 95% CI 1.01-2.09; p < 0.05). Even so, Gao et al. [36] and Stamatakis et al. [28] constitute that the relationship between television viewing and loftier fasting glucose and Hb1Ac was not statistically significant.

Cholesterol ratio and total

Gao et al. [36] demonstrated that greater time in television viewing was associated with a high total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio (OR two.0; 95% CI ane.1-iii.7; p < 0.05). In Stamatakis et al.'s [28] study, self-reported total leisure-fourth dimension sedentary behavior (β 0.018; 95% CI 0.005-0.032), television viewing (β 0.021; 95% CI 0.002-0.040), and objectively assessed sedentary behavior (β 0.060; 95% CI 0.000-0.121) were associated with cholesterol ratio. However, Gennuso et al. [39] institute that the relationship between time spent in sedentary beliefs and total cholesterol was not statistically significant (p = 0.l).

Other cardiometabolic biomarkers

The association between objectively measured sedentary time and pericardial fat [33] and coronary avenue calcification [34] was not observed after adjusting for moderate to vigorous physical activity. Gennuso et al. [39] constitute a positive association between sedentary hours and C-reactive protein (p < 0.01).

Waist circumference/waist-to-hip ratio/intestinal obesity

Six cross-sectional studies, [25, 26, 28, 30, 36, 39] classified as being of very depression [25, 26, 28, xxx] and of moderate [36, 39] quality, investigated the relationship between sedentary behavior and waist circumference/waist-to-hip/abdominal obesity.

Gardiner et al. [25] and Gomez-Cabello et al. [30] found that sitting fourth dimension increased the take chances of abdominal obesity past eighty% (OR i.viii; 95% CI 1.20-two.64) in both sexes and 81% in women (OR 1.81; 95% CI i.21-two.70).

In Stamatakis et al.'due south [28] study, idiot box time (β 0.416; 95% CI 0.275 - 0.558) and total cocky-reported leisure-time sedentary behavior (β 0.234; 95% CI 0.129 - 0.339) were positively related to waist circumference. Gao et al. [36] institute that greater time in television viewing was associated with loftier waist-to-hip ratio (3.9; 95% CI ane.08 - 8.4; p < 0.01). Gennuso et al. [39] found that more time spent in objectively measured sedentary beliefs was associated with a high waist circumference (p < 0.01). In a colorectal cancer survivor population, [26] sedentary time was not associated with waist circumference.

Overweight/obesity

Six cross-sectional studies, [28–31, 36, 37, 39] classified as existence of very depression [28–31, 37] and of moderate [36, 39] quality, investigated the relationship between sedentary behavior and overweight/obesity.

Gomez-Cabello et al. [30] demonstrated that sitting more than 4 hours/solar day increased the risk of overweight (OR ane.7; 95% CI 1.06-2.82) and obesity (OR 2.vii; 95% CI 1.62-4.66). In a similar written report, Gomez-Cabello et al. [31] showed that being seated more than 4 hours/day increased the run a risk of overweight/obesity (OR i.42; 95% CI 1.06-1.89) and overfat (1.4 OR; 95% CI 1.14-1.74) in women and the adventure of fundamental obesity (OR i.74; 95% CI i.21 – two.49) in men.

Gennuso et al. [39] found that more than time spent in considerately measured sedentary behavior was associated with higher BMI (p < 0.01). In Stamatakis et al.'due south [28] study, cocky-reported leisure-fourth dimension sedentary behavior (β 0.088; 95% CI 0.047 - 0.130) was associated with BMI.

Inoue et al. [37] found that when compared with the reference category (high telly(TV)/bereft moderate to vigorous physical action (MVPA)), the adjusted ORs (95% CI) of overweight/obesity were 0.93 (95% CI 0.65-one.34) for high Television/sufficient MVPA, 0.58 (95% CI 0.37-0.90) for depression Telly/insufficient MVPA, and 0.67 (95% CI 0.47-0.97) for low TV/sufficient MVPA. Stamatakis et al. [28] besides showed that TV fourth dimension (β 0.159; 95% CI 0.104-0.215) was positively associated with BMI. Notwithstanding, only Gao et al. [36] establish that greater time of television viewing was statistically significantly clan with BMI (OR 1.iv; 95% 0.vii-2.8).

In the only report that evaluated sedentary behavior in ship, Frank et al. [29] showed that ≥1 hr/solar day sitting in cars was not associated with overweight (0.86 OR. 95% CI 0.51-i.22) or obesity (0.67 OR; 95 CI% 0.41-one.06).

Mental health (Dementia, mild cerebral impairment, psychological well-beingness)

Three cantankerous-sectional studies, [32, 38, forty] one case–control, [41] and two prospective accomplice studies, [42, 47] classified as very depression [32, 41] and low quality [38, 40, 42, 47] investigated the relationship between sedentary behavior and mental health (dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and psychological well-beingness).

In Verghese et al.'s [47] study, individuals who oftentimes played board games (HR 0.26; 95% CI 0.17-0.57) and read (Hour 0.65; 95% CI 0.43-0.97) were less likely to develop dementia.

Buman et al. [32] demonstrated that sedentary fourth dimension was negatively associated with psychosocial well-being (β -0.03; 95% CI −0.05 - -0.01); p < 0.001. Still, Dogra et al. [38] found that four hours or more of sedentary beliefs per 24-hour interval was non associated with psychologically successful aging.

With regards to mild-cognitive harm (MCI), reading books (OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.49-0.94), playing lath games (OR 0.65; 95% CI 0.47-0.90), craft activities (OR 0.66; 95% CI 0.47-0.93), reckoner activities (OR 0.50; 95% CI 0.36-0.71), and watching television (OR 0.48; 95% CI 0.27-0.86) were significantly associated with a decreased odds of having MCI [forty]. According to Geda et al.'southward [41] study, physical exercise and figurer use were associated with a decreased likelihood of having MCI (OR 0.36; CI 95% 0.20-0.68).

However, Balboa-Castillo et al. [42] found that the highest quartile of sitting time was negatively associated with mental health (β-five.04; 95% CI −8.87- -1.21); p trend = 0.009.

Cancer

Just one study, with moderate quality, establish no association betwixt time watching television set or videos and renal cell carcinoma [27].

Discussion

To the all-time of our knowledge, this is the showtime systematic review to examine the association betwixt sedentary behavior and wellness outcomes in older people while considering the methodological quality of the reviewed studies. Like to previous reviews in adults, [16–19, 48] the nowadays review shows observational evidence that greater time spent in sedentary activities is related to an increase take a chance of all-crusade mortality in the elderly. However, in these studies, sedentary behavior was measured through self-reported questionnaires (e.g., hours/day of sitting time), which have moderate benchmark validity [49]. Studies with a moderate quality of evidence showed a relationship between sedentary behavior and metabolic syndrome, waist circumference, and overweight/obesity. The findings for other outcomes, such as mental health, renal cancer cells, and falls, remain insufficient to depict conclusions.

Nonetheless, some sedentary activities (due east.k., playing board games, craft activities, reading, calculator use) were associated with a lower take a chance of dementia [47]. Thus, future studies should have into account not only the amount of fourth dimension spent in sedentary beliefs but the social and cognitive context in which the activities takes identify [50]. To illustrate this bespeak, some studies take shown that video game and calculator use, even though classified as sedentary past free energy expenditure criteria, may reduce the gamble of mental wellness disorders [51–53].

Methodological issues

To overcome the limitations of the observational studies available, futurity longitudinal studies with a high methodological quality are required. Moreover, the primary limitations constitute in the reviewed articles should be taken into account in future studies (Boosted file 4). Based on these limitations, we offering several recommendations for hereafter studies.

Choice bias

In nearly one-half of the reviewed articles (x articles: 42%), the following selection biases were establish: a depression response rate; the use of independent and non-institutionalized volunteer participants; and an underrepresentation of some population subgroups [25, 27–29, 31–34, 37, 41, 47].

Data bias

To date, the use of accelerometers is the most valid and reliable method for evaluating sedentary behavior, although some devices are not able to distinguish sitting and standing posture [54]. In studies of the elderly, five days of accelerometer use seems to be sufficient to evaluate the blueprint of sedentary behavior [55]. When using accelerometers, futurity studies should clearly specify the criteria established for non-habiliment time [56] and use the most accurate sedentary cut-points (150 counts/min) [57] to avoid misclassification. In the current review, all studies used at least 7 days of accelerometry, with a non-wear time criteria of 60 minutes without counts and sedentary cut-points of <100 counts/minute [26, 28, 32, 37, 39] or <199 counts/minute [33, 34].

Although subjective measurements present a low to moderate reliability, they allow for the evaluation of the contextual dimension of the sedentary activities [49]. In the nowadays review, information bias attributable to self-reported instruments was found in xx articles (83%) [25–27, 29–34, 37, 38, 42–44, 40, 41, 45–47]. In this sense, emergent objective methods (e.g., combination of geolocation data combined with acceleration signals in mobile phone) have been developed to obtain a precise and meaningful characteristic of the patterns of sedentary behavior [49].

In improver, most of the studies in this review used different categorization criteria when measuring sedentary behavior [43–46]. This variation in categorization criteria could limit hereafter synthesis of the evidence. We recommend that future studies on the elderly use existing categorizations of sedentary behavior.

Imprecision

To reduce random mistake, future epidemiological studies, especially with longitudinal designs, should use an acceptable sample size. In the present review, 14 (58%) studies presented imprecise results [25–27, 29–31, 34–39, 41, 42].

Inconsistency

Subgroup and heterogeneity analysis should be performed and reported in hereafter studies to evaluate the consistency of the findings. In the electric current study, only i commodity presented the consistency of the findings between subgroups [25].

Indirectness: In the electric current review, indirectness (surrogate outcomes) was present in 17 articles (71%) [25–37, 39–41]. Importantly, conclusions obtained with surrogate markers just allow a better understanding of the sedentary beliefs physiology. Still, researchers should not consider these surrogate markers as synonymous with the endpoint outcomes [58].

Thus, endpoint outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular events, cancer and mortality) should exist addressed in time to come studies.

Confounding aligning

The confusion of effects (confounding) is a key issue in epidemiology. Although all of the studies in the present review included some covariates, such as moderate to vigorous physical activity, some residuum misreckoning may be present [59]. Moreover, health status should exist measured and included equally a covariate, especially in studies of the elderly to avert confounding [59]. Although most of the articles received improve quality scores when they adjusted for potential confounders, [25–29, 32–twoscore, 42–47] merely 3 studies included wellness condition every bit a covariate [25, 45, 46]. Futurity observational studies should include these important covariates in their statistical analysis.

Dose–response

Although sedentary behavior is a continuous variable, most of the studies categorized it every bit either an ordinal or a dummy variable. Such categorization could be an important limitation [60, 61]. However, if future studies opt to categorize, they should use pocket-size intervals with more homogeneous groups that may allow for the ascertainment of a dose–response slope betwixt sedentary behavior and health outcomes. In the present review, a dose–response was detected in 5 articles [36, 39, 42, 45, 46].

Conclusion

This review confirms previous evidence of the relationship betwixt sedentary behavior and all-cause mortality among adults. Due to the moderate quality of the studies, weak evidence exists regarding other health outcomes (metabolic syndrome, cardiometabolic biomarkers, obesity, and waist circumference). Nevertheless, of note, some sedentary activities (eastward.1000., playing board games, arts and crafts activities, reading, and computer use) had a protective human relationship with mental wellness status (dementia). Futurity studies should consider the main methodological limitations summarized in this review to improve the current land of the art. Finally, intervention trials that back up the observational noesis are needed to create informed guidelines for sedentary behavior in the elderly.

Authors' data

LFMR is a primary'due south student in the Department of Preventive Medicine - University of São Paulo School of Medicine. JPRL is a mail service-doctoral student in the Department of Preventive Medicine - University of São Paulo School of Medicine. VKRM is a scientific coordinator of CELAFISCS. OCL is a scientific researcher in the Department of Preventive Medicine - University of São Paulo School of Medicine.

Abbreviations

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

- LILACS:

-

Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde

- SBRD:

-

and the Sedentary Beliefs Research Database (SBRD)

- SBRN:

-

Sedentary Behaviour Inquiry Network

- Form:

-

Grades of Recommendation

- Cess:

-

Development and Evaluation

- Hr:

-

Take chances Ratio

- RR:

-

Relative Hazard

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- HDL:

-

High Density Lipoprotein

- MVPA:

-

Moderate to vigorous physical activity

- Tv:

-

Television

- BMI:

-

Trunk mass index

- MCI:

-

Mild-cognitive impairment.

References

-

Scully T: Demography: to the limit. Nature. 2013, 492: S2-S3. doi:10.1038/492S2a

-

WHO: Global Historic period-friendly Cities: A Guide. 2007, Geneva: WHO press

-

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics: Older Americans 2012: Key Indicators of Well-Existence. 2012, Washington, DC: U.S: Federal Interagency Forum on Crumbling-Related Statistics

-

WHO: Proficient Wellness Adds Life to Years: Global Cursory for World Health Day 2012. 2012, Geneva: WHO press

-

WHO: Global Recommendations on Concrete Activity for Health. 2010, Geneva: WHO press

-

Dishman RK, Health GW, Lee IM: Physical Activity Epidemiology. 2013, Champaign, IL: Man Kinetics, 2

-

Katzmarzyk PT: Physical activity, sedentary beliefs, and health: paradigm paralysis or paradigm shift?. Diabetes. 2010, 59: 2717-2725. 10.2337/db10-0822.

-

Owen North: Sedentary behavior: understanding and influencing adult'due south prolonged sitting time. Prev Med. 2012, 55: 535-539. ten.1016/j.ypmed.2012.08.024.

-

Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dustan DW: Also much sitting: the population wellness science of sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2010, 38: 105-113. 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2.

-

Pate RR, O'Neill JR, Lobelo F: The evolving definition of "sedentary". Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2008, 36: 173-178. 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181877d1a.

-

Rhodes RE, Mark RS, Temmel CP: Adult sedentary behavior a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012, 42: E3-E28. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.020.

-

Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, Buchowski MS, Beech BM, Pate RR, Troiano RP: Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United states, 2003–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008, 167: 875-881. 10.1093/aje/kwm390.

-

LeBlanc AG, Spence JC, Carson V, Connor Gorber South, Dillman C, Janssen I, Kho ME, Stearns JA, Timmons BW, Tremblay MS: Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in the early years (anile 0–4 years). Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012, 37: 753-772. ten.1139/h2012-063.

-

Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, Saunders TJ, Larouche R, Colley RC, Goldfield G, Connor Gorber S: Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Human action. 2011, 8: 98-10.1186/1479-5868-8-98.

-

Marshall SJ1, Biddle SJ, Gorely T, Cameron N, Murdey I: Relationships betwixt media use, torso fatness and physical activity in children and youth: A meta-analysis. Int J Obesity. 2004, 28: 1238-1246. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802706.

-

Thorp AA, Owen N, Neuhaus Grand, Dustan DW: Sedentary behaviors and subsequent health outcomes in adults a systematic review of longitudinal studies, 1996–2011. Am J Prev Med. 2011, 41: 207-215. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.004.

-

Grontved A, Hu FB: Tv viewing and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and all-crusade bloodshed A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011, 305: 2448-2455. 10.1001/jama.2011.812.

-

Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, Davies MJ, Gorely T, Gray LJ, Khunti G, Yates T, Biddle SJ: Sedentary fourth dimension in adults and the clan with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and expiry: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2012, 55: 2895-2905. 10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z.

-

Lynch BM: Sedentary behavior and cancer: a systematic review of the literature and proposed biological mechanisms. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010, 19: 2691-2709. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0815.

-

Nybo H, Petersen HC, Gaist D, Jeune B, Andersen K, McGue M, Vaupel JW, Christensen K: Predictors of bloodshed in2,249 nonagenarians – the Danish 1905-Cohort Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003, 51: 1365-1373. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51453.10.

-

Davis MG, Fox KR, Hillsdon M, Sharp DJ, Coulson JC, Thompson JL: Objectively measured physical activity in a various sample of older urban Britain adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001, 43: 647-654.

-

McLennan W, Podger A: National nutrition survey users' guide. Catalogue No 48010. 1998, Canberra, Human activity: Australian Bureau of Statistics

-

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Balderdash FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U: Global concrete activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012, 380: 247-257. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1.

-

Guyatt GH, Oxman Ad, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knotterus A: Class guidelines: A new serial of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011, 64: 380-382. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011.

-

Gardiner PA, Healy GN, Eakin EG, Clark BK, Dunstan DW, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Owen N: Associations between tv set viewing fourth dimension and overall sitting fourth dimension with the metabolic syndrome in older men and women: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011, 59: 788-796. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03390.10.

-

Lynch BM, Dunstan DW, Winkler East, Healy GN, Eakin E, Owen N: Objectively assessed physical activity, sedentary time and waist circumference among prostate cancer survivors: findings from the National Wellness and Nutrition Examination Survey (2003–2006). Eur J Cancer Care. 2011, 20: 514-519. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01205.x.

-

George SM, Moore SC, Grub WH, Schatzkin A, Hollenbeck AR, Matthews CE: A prospective analysis of prolonged sitting time and take chances of renal cell carcinoma among 300,000 older adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2011, 21: 787-790. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.04.012.

-

Stamatakis E, Davis Thou, Stathi A, Hamer Thou: Associations between multiple indicators of objectively-measured and self-reported sedentary behaviour and cardiometabolic take chances in older adults. Prev Med. 2012, 54: 82-87. ten.1016/j.ypmed.2011.10.009.

-

Frank Fifty, Keer J, Rosenberg D, Rex A: Healthy aging and where you live: community pattern relationships with physical activity and torso weight in older Americans. J Phys Act Health. 2010, vii (Suppl i): S82-S90.

-

Gomez-Cabello A, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Pindado 1000, Vila S, Casajús JA, Pradas Dela Fuente F, Ara I: Increased risk of Obesity and fundamental obesity in sedentary postmenopausal Women. Nutr Hosp. 2012, 27: 865-870.

-

Gomez-Cabello A, Pedreto-Chamizo R, Olivares PR, Hernández_Perera R, Rodríguez-Marroyo JA, Mata E, Aznar South, Villa JG, Espino-Torón Fifty, Gusi N, González G, Casajús JA, Ara I, Vicente-Rodríguez G: Sitting time increases the overweight and obesity take a chance independently of walking fourth dimension in elderly people from Espana. Maturitas. 2012, 73: 337-343. x.1016/j.maturitas.2012.09.001.

-

Buman MP, Hekler EB, Haskell WL, Pruitt L, Conway TL, Cain KL, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD, King AC: Objective light-intensity physical activity associations with rated health in older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2010, 172: 1155-1165. x.1093/aje/kwq249.

-

Hamer M, Venuraju SM, Urbanova L, Lahiri A, Steptoe A: Physical activeness, sedentary fourth dimension, and pericardial fat in salubrious older adults. Obesity. 2012, xx: 2113-2117. 10.1038/oby.2012.61.

-

Hamer M, Venuraju SM, Lahiri A, Rossi A, Steptoe A: Considerately assessed concrete activeness, sedentary time, and coronary avenue calcification in salubrious older adults. Artriolscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012, 32: 500-505. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.236877.

-

Bankoski A, Harris TB, McClain JJ, Brychta RJ, Caserotti P, Chen KY, Berrigan D, Troiano RP, Koster A: Sedentary activity associated with metabolic syndrome independent of concrete activity. Diabetes Care. 2011, 34: 497-503. ten.2337/dc10-0987.

-

Gao X, Nelson ME, Tucker KL: Television viewing is associated with prevalence of metabolic syndrome in hispanic elders. Diabetes Care. 2007, thirty: 694-700. 10.2337/dc06-1835.

-

Inoue S, Sugiyama T, Takamiya T, Oka Thou, Owen N, Shimomitsu T: Television viewing time is associated with overweight/obesity among older adults, contained of meeting physical activity and wellness guidelines. J Epidemiol. 2012, 22: l-56. 10.2188/jea.JE20110054.

-

Dogra Southward, Stathokostas Fifty: Sedentary behavior and physical activity are independent predictors of sucessful aging in middle-aged and older adults. Crumbling Res. 2012, 2012: 190654-

-

Gennuso KP, Gangnon RE, Matthews CE, Thraen-Borowski KM, Colbert LH: Sedentary beliefs, physical activity, and markers of health in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013, 45: 1493-

-

Geda YE, Topazian HM, Roberts LA, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Pankratz VS, Christianson TJ, Boeve BF, Tangalos EG, Ivnik RJ, Petersen RC: Engaging in cognitive activities, aging, and mild cognitive harm: a population based study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011, 23: 149-154. 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.23.2.149.

-

Geda F, Silber TC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Christianson TJ, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, Tangalos EG, Petersen RC: Computer activities, physical exercise, crumbling, and mild cognitive impairment: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012, 87: 437-442. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.12.020.

-

Balboa-Castillo T, León-Munoz LM, Graciani A, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Guallar-Castillón P: Longitudinal association of physical activeness and sedentary behavior during leisure time with wellness-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011, 27: 9-47.

-

Campbell PT, Patel AV, Newton CC, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM: Associations of recreational physical activity and leisure time spent sitting with colorectal cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2013, 31: 876-885. 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9735.

-

Martinez-Gomez D, Guallar-Castillón P, León-Munoz LM, López-Garcia E, Rodríguez-Artalejo F: Combined impact of traditional and non-traditional health behaviors on mortality: a national prospective accomplice study in Spanish older adults. BMC Med. 2013, 22: 47-

-

Pavey TG, Peeters GG, Brownish WJ: Sitting-time and 9-year all-cause bloodshed in older women. Br J Sports Med. 2012, 0: 1-5.

-

León-Muñoz LM, Martínez-Gómez D, Balboa-Castillo T, López-García East, Guallar-Castillón P, Rodríguez-Artalejo F: Continued sedentariness, alter in sitting time, and mortality in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013, 45: 1501-1507.

-

Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Hall CB, Derby CA, Kuslansky Grand, Mabrose AF, Sliwinski M, Buschke H: Leisure Activities and the Risk of Dementia in the Elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003, 348: 2508-2516. 10.1056/NEJMoa022252.

-

Proper KI, Singh Every bit, Van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ: Sedentary behaviors and health outcomes amid adults: a systematic review of prospective studies. Am J Prev Med. 2011, 40: 174-182. x.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.015.

-

Atkin AJ, Gorely T, Clemes SA, Yates T, Edwardson C, Brage S, Salmon J, Marshall SJ, Biddle SJH: Methods of measurement in epidemiology: sedentary behaviour. Int J Epidemiol. 2012, 41: 1460-1471. 10.1093/ije/dys118.

-

Gabriel KKP, Morrow JR, Woolsey AL: Framework for concrete action as a circuitous and multidimensional behavior. J Phys Act Health. 2012, nine (Suppl 1): S11-S18.

-

Anguera JA, Boccanfuso J, Rintoul JL, Al-Hashimi O, Faraji F, Janowich J, Kong E, Larraburo Y, Rolle C, Johnston E, Gazzaley A: Video game training enhances cognitive control in older adults. Nature. 2013, 5: 97-101.

-

Kueider AM, Parisi JM, Gross AL, Rebok GW: Computerized cognitive training with older adults a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e40588-10.1371/periodical.pone.0040588.

-

Primack BA, Carroll MV, McNamara M, Klem ML, King B, Rich M, Chan CW, Nayak Southward: Part of video games in improving health-related outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012, 42: 630-638. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.023.

-

Wong SL, Colley R, Connor Gorber Due south, Tremblay Thousand: Actical accelerometer sedentary activity thresholds for adults. J Phys Human activity Health. 2011, viii: 587-591.

-

Hart TL, Swartz AM, Cashin SE, Strath SJ: How many days of monitoring predict physical activity and sedentary behaviour in older adults?. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Deed. 2011, 8: 62-x.1186/1479-5868-8-62.

-

Mâsse LC, Fuemmeler BF, Anderson CB, Matthews CE, Trost SG, Catellier DJ, Treuth M: Accelerometer information reduction: a comparison of four reduction algorithms on select outcome variables. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005, 37: S544-S554.

-

Kozey-Keadle S, Libertine A, Lyden K, Staudenmayer J, Freedson PS: Validation of habiliment monitors for assessing sedentary behavior. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011, 43: 1561-1567.

-

Yudkin J, Lipska Thou, Montori V: The idolatry of the surrogate. BMJ. 2011, 343: d7995-ten.1136/bmj.d7995.

-

Andrade C, Fernandes P: Is sitting harmful to health? It is too early to say. Curvation Int Med. 2012, 172: 1272-

-

Dinero TE: Seven reasons why you should not categorize continous information. J Health Soc Policy. 1996, viii: 63-72. 10.1300/J045v08n01_06.

-

Altman D, Royston P: The toll of dichotomisng continous variables. BMJ. 2006, 332: 1080-

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this newspaper can exist accessed hither:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/333/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Sedentary Behaviour Research Network members for sending us titles of studies that were potentially eligible for inclusion in our systematic review. This study received financial back up from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP, São Paulo Research Foundation; Grant no. 2012/07314-8).

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Boosted information

Competing interests

No financial disclosures were reported past the authors of this paper.

Authors' contributions

Report Concept and design: LFMR, OCL; Search Strategy: LFMR; Identification and Selection of the Literature: LFMR, JPRL; Data Extraction and Quality Assessment: LFMR, JPRL; Narrative Synthesis: LFMR, JPRL; Drafting of the Manuscript: LFMR, JPRL; Report Supervision: OCL, VKRM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This commodity is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original piece of work is properly credited. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zilch/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Rezende, Fifty.F.M.d., Rey-López, J.P., Matsudo, V.Grand.R. et al. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes amidst older adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Wellness fourteen, 333 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-xiv-333

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/1471-2458-xiv-333

Keywords

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Sitting time

- Television

- Hazard factors

- Anile

- Health status

- Bloodshed

bernardimpeartale.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-14-333

0 Response to "Sedentary Lifestyle Related to Succesful Again G"

Post a Comment